|

Graduate school thus far has been an adventure for sure. There has been ups and downs, a real rollercoaster effect. In fact, I would be lying if I said that I never wanted to quit (I may still joke about it to this day). Is it because grad school is hard? Of course! But I think that it is more than that. In part, I believe it is because I had no idea what grad school involved. As a first-generation college student, I had no clue what grad school was or why it was necessary (or not necessary). Nor did I know that in the sciences you get a Ph.D. for FREE... yes for FREE. In fact, they pay you! It is crazy, right?!?!? Then why doesn't everyone get a Ph.D.? Is it because you must be a super genius? NO-not all. I mean you have to be a good student, but by no means a genius. So why is the world not all walking around as Ph.D.'s? It is because it is HARD (duh, right?) or takes a long time (YES!)? But it is much more than academically challenging, it is also mentally, emotionally, and physically challenging. It takes so much more than I ever realized, in fact it takes all of me. But this does not mean it is not worth it, nor would I take it back. This experience has been unlike anything I have ever done or will do. It has come with amazing opportunities and will (hopefully) open even more doors in the future. But I think that you must really want to get a Ph.D., to truly appreciate the opportunities. If you are just doing it "to do it" you will find yourself beyond stressed and utterly unhappy. Science requires a love of what you are doing or, at the very least, a belief that what you are doing matters. As I reflect back on the last three years, I wish there were things that I would have known before coming to grad school. Things that I really cannot change, but that knowing them would have prepared me for the road ahead. I thought that others would benefit from knowing some of these things, so here are 5 things that I wish I knew before committing to getting a Ph.D.

1. Graduate School is a Lifestyle I cannot not emphasis this enough! You do not simply just go to school. When you are in undergrad you go to classes, study hard, and maybe do some extracurricular activities. You get fall and spring breaks and summer off. Not downplaying the accomplishment of getting a bachelor’s degree, because it is an amazing accomplishment and it is hard. But you do not live and breathe it, you may worry about a test or a project but there is still Netflix binges and nights out (maybe more then we all want to admit). Graduate school is completely different. It is hard to put into words, but it is basically just one continuous semester on the same subject. You do not get blocks of time off. In fact, most of the time it takes the university being closed, and honestly this is my favorite time to work because no one is there! This sounds horrible, like forced labor, right? It really is not. You can still take a personal day or a vacation, but it is not an outlined, scheduled thing. These times off are to be worked out between you and your PI (i.e. boss), the person you do research for, and honestly are hard to enjoy because self-guilt often creeps in. "I should be working.." "I am never going to get any data if I take time off.." "now I am behind schedule.." It is often hard to ignore the guilt and sometimes you find that you are your own worst enemy. But while on the topic of time off and amount of time spent working, I highly recommend you confirm expectations with your PI before entering a lab. All labs are run differently and the expectations varies from lab to lab. There is no right or wrong and it is important that you find a place that fits your expectations of grad school and an environment that you can grow in. This is so very important and is different for everyone. For example, I have 2 young kids and needed a boss that understood that sometimes things come up unexpectedly (illness, injury, cancelled baby sitter, etc.), luckily I have just that! I would never had made it this far if I had a boss that was not flexible (and trust me they are out there). The understanding and flexibility my PI shows me, makes me work even harder because I appreciate her understanding that "life happens". Now back to science as a lifestyle. You will live and breathe your science. You simply do not go to school for 8 hours and shut off after you leave. Not to say that there is no work-life balance, but I will be honest in saying that it is sometimes extremely difficult to maintain. You will find yourself thinking about your upcoming experiment or reading journal articles way later into the night then you anticipated. Simply put -- you will have moments or days or weeks where you are completely consumed. It is truly impossible to avoid. I mean this is all you do for years and years, and you are invested in it. Plus, unlike undergrad, you do not simply graduate, you have to make "a contribution to your field". *Cue pressure* So not only am I living and breathing my science, but it must mean something too? This can quickly lead you down a rabbit hole. BE AWARE OF THE RABBIT HOLE. Make sure you surround yourself with people who can get you out of said hole. Grad school is so much more than research. This is where the lifestyle part comes in. There are certain expectations that are placed on you as a graduate student. You must attend departmental events and host speakers. Attend seminars and social events. You are expected to volunteer in student-run activities and recruitment weekends. While also juggling research, classes or qualification exams, teaching loads (if you are not on RA), and mentoring of undergrads. Additionally, you have to go out and disseminate your science if you ever want to establish a professional network. This involves attending scientific conferences and presenting your research, all the while trying to figure out how to pay for said conference (and why is it so expensive, honestly do we have to charge $500 to attend a conference where all (or most) of the presenters do it for free??). You will quickly find that your schedule looks busier than a doctor’s office schedule during flu season. And you will ask yourself, "how can I do this all? There is simply no way". But you will find that not only can you do it, but that you are probably good at it. My advice: One day at a time. But as a mom, this was hard for me to get use too. Not only because I had no idea that it was a thing, but because my time is already ready filled with school drop off, dance, and swim lessons. I did not come to grad school to find myself or make friends (not to say that I haven't). I came to get a Ph.D. and I thought that meant research and classes. I did not want to stay late on Friday's to socialize or take recruits on "a night on the town". I must say that I am lucky to be in a department that respects that I have a family and does not demand my time when my family needs it. But I think that it is important to be aware that these kind of events and requirements exist and know that you do not just "simply go home" at the end of the day. 2. No One Outside of Academia Will Understand When I first started my program, we had to take an "Intro to grad" course that was aimed at helping us adjust to being grad students. During this class, we were provided a paper to read that was advise on grad school. Within this document was a statement that at the time seemed utterly ridiculous. The paper stated something like "You will begin to find that no one outside of academia will be able to relate to you or you to them". This seemed virtually impossible. Why would that happen, it is not like I am going to magically be a different person? I am not going far away or undergoing some miraculous transformation. But little did I know, that there was nothing more accurate in that entire paper than that statement. How does this disconnect happen? I think it is caused by several things. First, you do change, not that it is a bad thing, but you do not undergo a process like getting a Ph.D. and not experience some level of growth. Besides everyone changes over time. I think another factor is what I discussed in my first point. You are grossly consumed on a specific topic and sometimes it is hard to shut that off. Other individuals in academia often do not notice this in you (or understand it because they are also consumed in their science), but to those outside of academia it is extremely apparent that you are not 100% "there". Your priorities no longer match your college friends or your cousin that was your childhood friend, your lives are in different places. The fact is that you are losing similar interests. Once again I do not think that this is unique to academia, people "grow apart all the time", but I do think that it is more of an apparent severing then you may have experienced in the past. You do not fade apart, you just hangout one day and realize that you are probably not going to hangout again. Kind of like when you have a baby and that "party friend" never calls again. These things happen all the time. Like with friends, extended family also have a difficult time relating. This is not because they do not care, they absolutely do and are so incredibly proud of you. It is just something, unless they have done it, that they will not comprehend. They will never understand how hard you had to work to get that single graph with a couple stars on top. They will not understand that you do not simply graduate after 4 years or that if all your experiments fail you start over. That there is no "A for effort". *Cue the uncomfortable questions* "You are STILL in school?" "When do you graduate?" "What do you mean you have to work the weekends, do you get paid overtime?" "Don't you have the summer off". No matter how many times you attempt to answer these questions, they will be asked of you every-single-time. It was one of those "laugh so that you do not cry situations". I want to take a minute to clarify this point. While in grad school you do not lose all your friends and stop attending all family events, but like having children, your priorities shift. It is in this shift that the circle of friends you keep may become different and some family events may become harder. Though this can be tough, there are always ROCKS in your life that remain sturdy. That no matter what they are there, they understand (or do their damnest to try), and know exactly what questions NOT TO ASK. They listen to you vent and understand sometimes you need to cry. Hold onto these people with 2 hands. These are the people that will get you through the lows and will celebrate the highs. These "rocks" come in all forms, a significant other, your sibling, or a parent. For me it is my husband, I cannot tell you how many times he has built me up when imposter syndrome creeped in (see below) and gave me a dose of brutal truth when I was being hysterical. I would not have made it this far in the program (or probably life) without him. To summarize, most people will not understand the process that is required to get a Ph.D. (and that is ok!), but you only need one rock to get to the finish line! 3. It Takes Much More than Smarts Before I ever even imagined getting a Ph.D. I thought only the super smart people, the prodigies, the geniuses got a doctorate. This is so not true. It is not to say that some very, very smart people have Ph.D.'s, but they are by no means limited to only gifted people. In fact, it is the uniqueness and diversity of people that have a Ph.D. that results in innovation and discovery! Could you imagine if everyone fit the same cookie cutter skills and abilities, in any field really? It would be awful and incredibly boring. I am also not saying that you do not have to work hard to get into a Ph.D. program, because you absolutely do. What I am saying is that you DO NOT have to be perfect! You are expected to have good grades and a decent GRE score. Most schools are not looking for straight A's (disclaimer I cannot comment on the standards for ivy league, I have never undergone that processes) and honestly a lot schools are beginning to eliminate the GRE's all together. Why? Because knowledge alone is not reflective of performance. A foundational knowledge, of course, is necessary so that you have something to build on, but you will spend 4-6 years "getting really smart" on a specific topic (i.e. become an expert!). Programs are in no way are already looking for an expert. Realizing it takes more than smarts is great news (unless you were only banking on your smarts I suppose J). But what else is required, what other skills are needed? While this is just based on my observations, I believe the following skills are useful: -organization -multi-tasking -good time management -playing well with others (team work) -independence/accountability -communication skills I do not think that you need to have all of the above skills, but having several of them are key. I also do not think that you need to be amazing at any or all of these, but just be capable of them. Your skills will continuously develop and emerge, but I think that grad school heavily relies on these skills for success and the more developed they are the easier the transition in grad school is. I will briefly address the above skills and why I think that they are desirable in grad school (and life in general). Organization- as I described above you have A LOT GOING ON and you must find a way to keep track of it. I highly recommend getting a good planner, one that allows you to keep track of not only appointments and classes, but daily tasks and goals. I swear by the Blue Sky daily & monthly planner and recommend it to everyone (I am not compensated for this suggestion, I really do just love it). It has a whole page for every single day (including a to do list section!) and still gives you the monthly calendar. Other people prefer digital calendars. Either way, having a plan for organization and keeping committed to it is key! Multi-tasking- For similar reasons as above, you have a lot going on. You need to be able to do more than one thing at a time. For some people this is extremely easy, but for others it does not come natural. It takes practice and that is ok, you will get plenty of practice in grad school. Either way it is important that you are capable of multi-tasking. If you have a culture of bacteria that needs to grow over night, that cannot be the only thing on your list for the day (also why organization is helpful) or the next day for that matter (what if it does not grow?). It is inevitable that you will be running several different experiments at one time, while also attending classes, meetings, seminar, etc.. The sooner you are capable of comfortably handling this, the better off you will be (not only in terms of progress, but mentally as well!). Good Time Management- this is closely related to organization and multi-tasking. Time management is connected to planning. I always layout what I am doing the next day before I leave the lab for the day. That way I have gone over what I am going to do the next day and what supplies I may need. This prevents "surprises" and allows me to assure that I can complete my goals tomorrow. If I needed an overnight culture for incubating samples the next day and I do not do that, I cannot do that experiment. It allows me to plan accordingly. Additionally, you can plan short tasks in between long incubation times. This allows you to get the most done by being efficient. Efficiency makes task completion a lot easier! Team work- This truly should not be a surprise. Like any other job, you must play well with others. This is of course just as important in grad school. Not only does research involve a team effort within a lab, but also across labs. Science often requires an interdisciplinary team to address the hypothesis and questions at hand (and funding agencies want to see this too). Collaborations are awesome! You want to make as many contacts as possible and you do this best by being a team player. That way, when you leave grad school you already have a record of team work (hopefully a paper trail in the form of publications). Independence/Accountability- Grad school requires a level of independence and accountability. You do not have someone holding your hand in every task, nor are you held to specific hours. In fact, you have a lot of freedom and flexibility (though the amount of flexibility varies lab to lab). You are expected to get what you need to get done and be where you need be. You may have weekly (or monthly or occasional) meetings with your PI, but outside of that you are expected to report on your progress to your committee ONCE A YEAR. That is correct 1/365 days. I was shocked when I heard that. Though that seems amazing (and in some ways, it is), it also leaves a lot of room for slacking. That is why you should keep yourself accountable. Set goals and keep them. You will have your PI and other mentors to keep you on track, but when it comes down to it, you must do it. Communication Skills- this is the one for me that was the most underdeveloped. Communication (especially public speaking) can be difficult, but for how difficult it is, it is equally as important. As a scientist, you need to communicate with peers, colleagues, granting agencies, and the community. Having good communication skills will continuously improve as you practice in the form of presenting, writing manuscripts and grants, and collaborations. Having a good foundation in communication will be invaluable in grad school. Of course, there are a lot of other skills and traits that make grad school just a little bit easier. There is no set list and it will vary from person-to-person. Do not read this list and set yourself into panic. Even without any of these skills at the start of grad school, grad school is possible but I believe development of these skills are extremely beneficial. 4. Imposter Syndrome Imposter syndrome is the feeling that you are an imposter (hence the name). That you are not good enough to be where you are and that you do not know what people think you know. It is this fear that creeps in and makes you feel like, at any moment, you are going to be exposed as the fraud you are. It comes and goes, creeping up as you achieve milestones or prepare for a conference. There are a lot of good information out there about imposter syndrome, so I am not going to spend a whole lot of time on this subject. The reason I included it is because it is a very real thing. What is even more surprising than its very existence, is the fact that it is extremely widespread AND almost everyone suffers from it at one point or another in academia. This makes sense though, right? As academics, you are viewed as experts (or working towards it) and this results in a certain level of expected pressure. What is a little discouraging is that imposter syndrome does not slowly go away as you get confident in your science, as you become an expert. In fact, many highly successful scientist (and celebrities, it is not exclusive to academics) have admitted to suffering from imposter syndrome. The key is to get ahead of it. Acknowledge it is exactly that, name it, and find ways to get past it. This is not easy, but it is not impossible. Not to say you are going to cure your imposter syndrome, but every moment without it is still winning! For ideas on how to silence the self-doubt, check out this awesome blog on ways to try to overcome imposter syndrome. 5. The Opportunities are Endless I wanted to make sure to end this article on a good note, I in no way intended this to be a deterrent from grad school. I think that grad school is equally as awarding, as it is challenging. I have found it to be a wonderful time of self-growth and personal development, not to say that it has been perfect (obviously from my current reflections). I think that one thing that I wish I knew before hand, that may have had me planning to get a Ph.D. all along, was that grad school brings a wealth of opportunities. I am not talking about after graduation, I mean right now as a grad student. One day you are a freshly graduated college student and the next day you're a graduate student. I am not sure what happens that make you so different in just one day, but one thing is clear – you are different. Suddenly, people look at you differently, treat you differently, and therefore provide far more opportunities. This may be more apparent to me because I went to grad school where I got my B.S., but in any case, I think that it is true. Professors now become colleagues (to a certain degree of course), but you are at least on a first name basis. You are looked to as a leader, a wealth of knowledge. By time you leave grad school, you are of course all those things, but it is a gradual process. Yet, there is no real tier system in grad school, it is more of a flat “grad student status”. Though this seems scary, in many ways it is fantastic. You have the power (and you should use it) to make a difference. You can mentor undergrad students, to inspire others how you have been inspired. Students looking to you for wisdom is a nice confidence builder as well and, trust me, you need it. Mentoring also provides you valuable (and marketable) skills for the future. To show that you are able teach and guide others is exactly what future employers (and granting agencies) want to see. There are opportunities for outreach as well. I am biased to this opportunity because I absolutely LOVE outreach. I think it is so incredibly important to bring STEM to the community. As a grad student, you can not only lead outreach events, but you organize them too. I have planned events start to finish, with no question in my ability to do so. There are other great opportunities that have come from grad school thus far, I have started this blog and the website it is hosted on, I have found a community of scientist on Twitter that shares an amazing wealth of knowledge, participated in "Meet as Scientist" Events at Phipps Conservatory, and I was involved in #scicomm events such as “I’m a Scientist, get me out of here” where I chatted with school edge children answering any and all questions they have. These are just a few opportunities that I may have never had if I was not in grad school (not to say it is impossible), that were at least in part inspired by grad school or simply through the exposure I received while in grad school. Everyone’s journey will be different, but in any case, I believe that there are unlimited opportunities in grad school -- you just need to find what interests you! In closing, graduate school is what you make of it. It can be a wonderful, exciting time or it can be a horrible experience. Or something in the middle, neither here-nor-there. Hopefully, knowing what is expected of you will help with the journey (would have helped me). However, if what you are doing feels forced or is truly a bad situation (unfortunately this can happen), make a change, you owe it yourself. In all things, stay true to yourself no matter what!

0 Comments

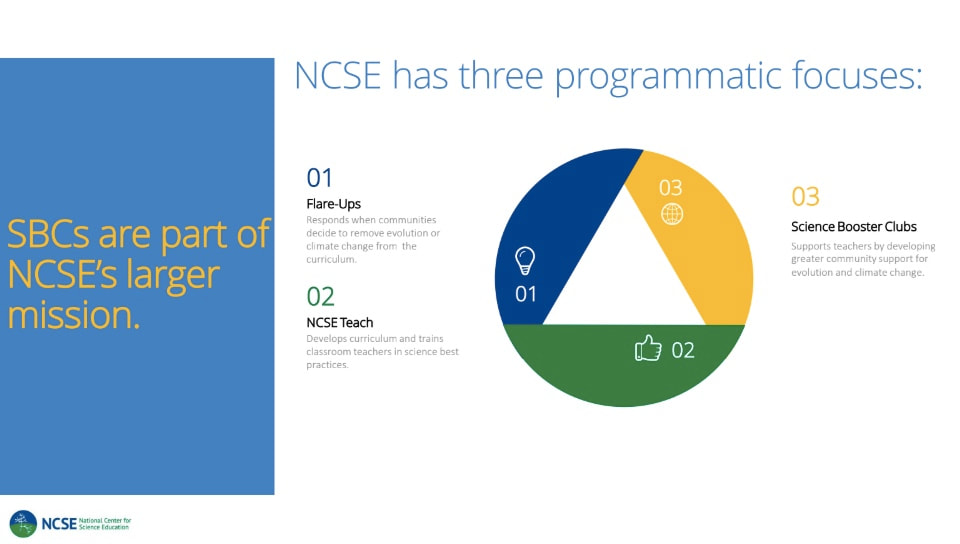

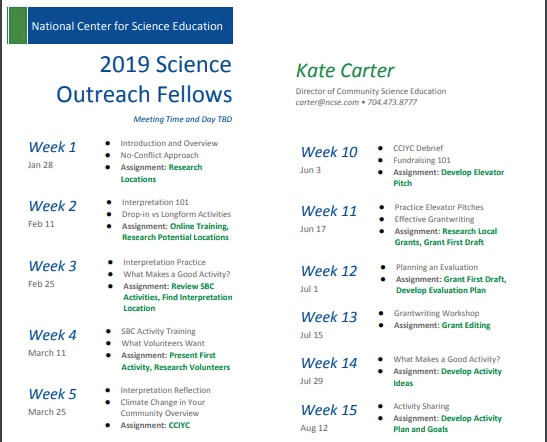

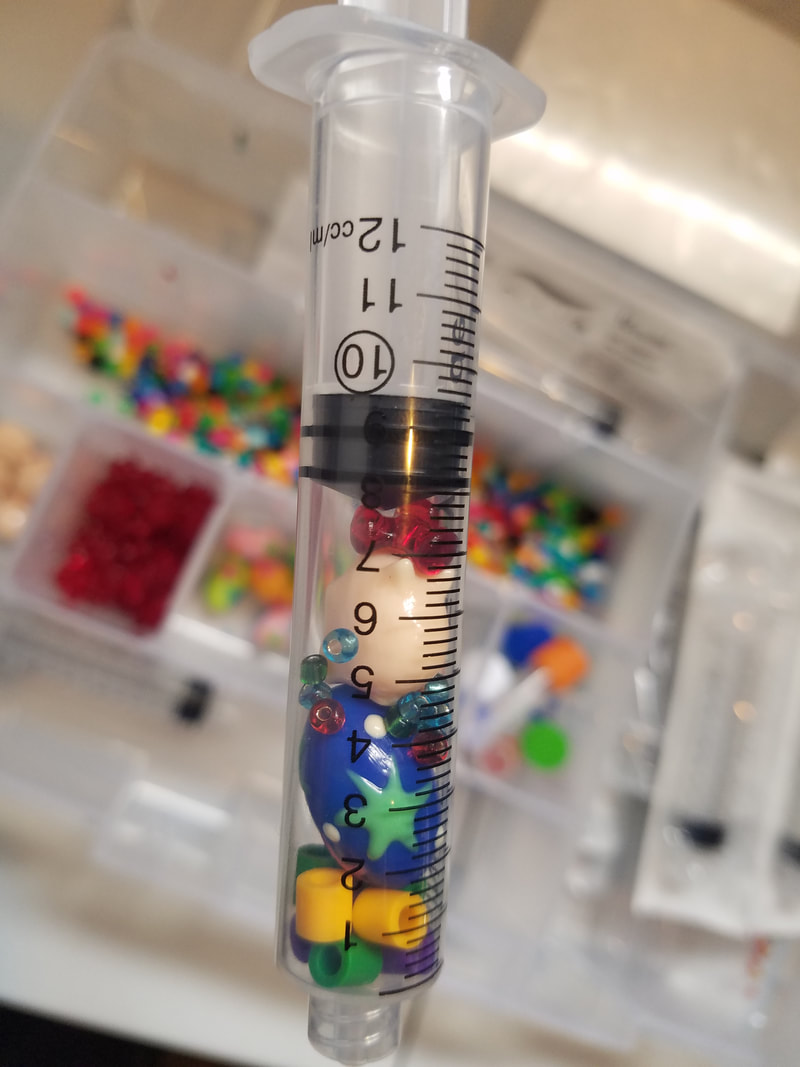

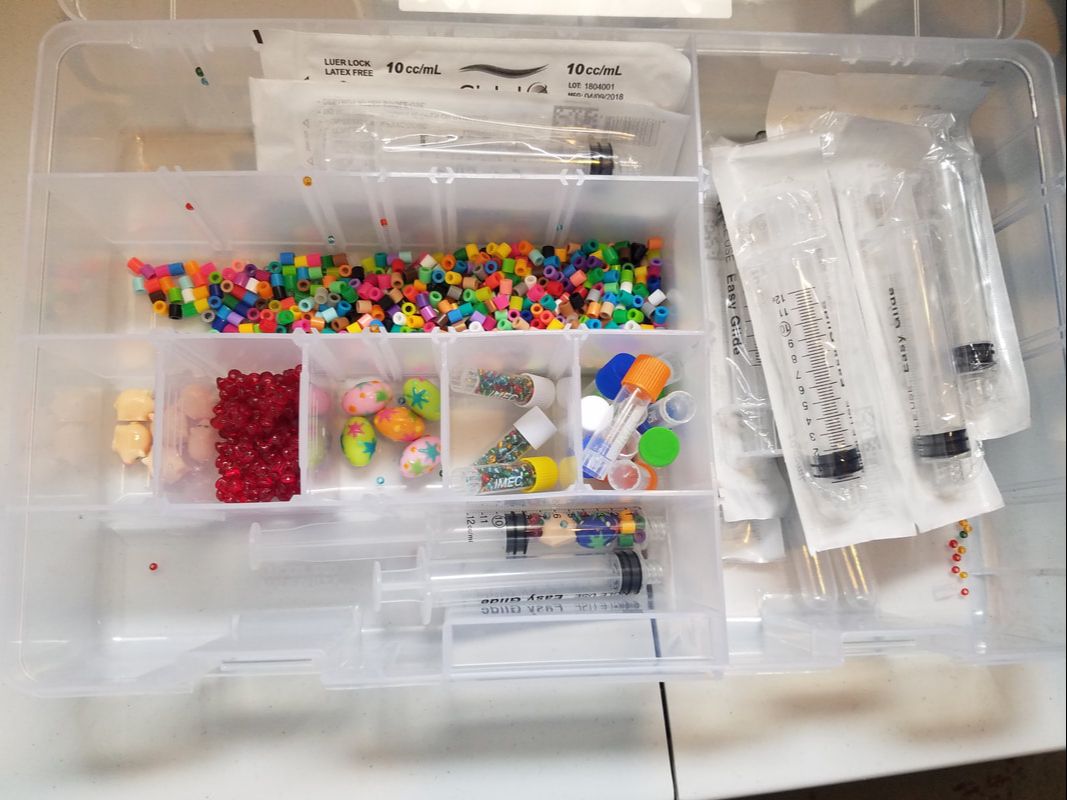

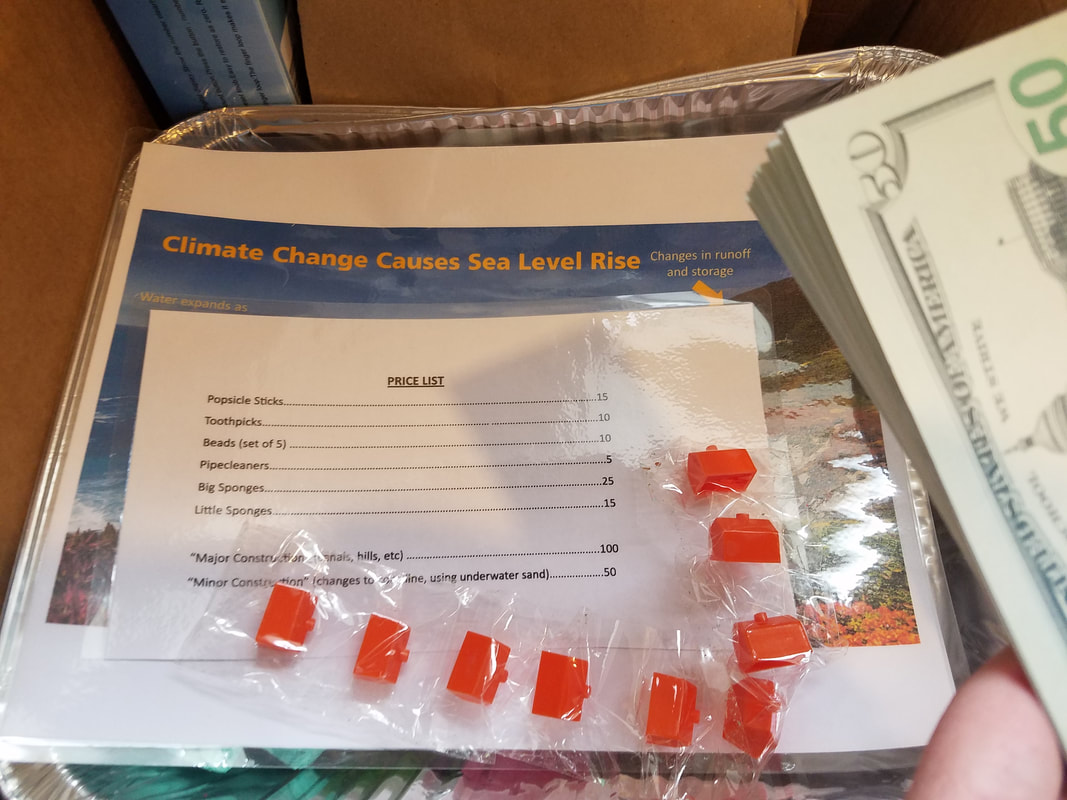

Over the course of this year, I am going to blog about my National Center for Science Education (NCSE) Science Communication Fellowship and share all the wonderful resources that I come across along the way. I am super excited for this opportunity, all of the skills I am going to gain, and the science communication events I am going to participate in. If it was not for twitter (shout out to @NMLaudicina), I would not have known about this opportunity. So I started to wonder how many people could really benefit and thoroughly enjoy this fellowship, that may have never heard of it. So before all of the awesomeness starts, I wanted to use this first blog post to talk a little about NCSE and what exactly the NCSE Science Communication Fellowship is. NCSE was first established in 1981 to help local communities assure that evolution was accurately being taught in the classroom. They have since taken on climate change as well, as it has been highly disregarded in much of the United States. Their mission states "NCSE promotes and defends accurate and effective science education, because everyone deserves to engage with the evidence." NCSE actively works to promote and support scientifically controversial topics, using a no-conflict approach. For more information on NCSE and the achievements in science that they have helped facilitate, you can click here. NCSE has three primary focuses. The first is "Flare-Ups". These are very specific incidences where a community needs the support of NCSE to prevent the removal of climate change or evolution from a classroom curriculum. These are unplanned events, that often require instant action. If you have a flare-up in your community, you can contact NCSE here. The second focus is "NCSE Teach". This was the focus that I was most familiar with. This branch of NCSE focuses on supplementing teachers with training and activities for evolution and climate change. They have programs that specifically teach teachers how to teach controversial subjects with no-conflict, they have programs that bring scientist and teachers together for "scientist in the classroom" activities, and they have a plethora of activities for evolution and climate change online that can be downloaded for use in the classroom or for STEM outreach. I highly recommend everyone take advantage of all of the resources available on the NCSE website . So what is the science communication fellowship? What does it involve? Well I am so glad that you asked! I am just starting out and of course will update you as I go along, but I do have an overview of what is going to occur throughout the year. So the fellowship runs for 12 months. My fellowship started January 1st, 2019 and will run to December 31, 2019. With that being said, it is not a yearly fellowship that runs at a set time. It is based on available funding. I was told that they believe that they will have the next open call in JULY (I will definitely tweet out as soon as I know for sure). The overall purpose of the fellowship is to start a booster club in your area. The booster club allows hands-on learning in the community, with the purpose of increasing science literacy. NCSE had booster clubs nationwide! Throughout the year, the fellowship asks that you meet biweekly through a video conference with the other fellows and the Director of Community Science Education, Dr. Kate Carter. We discuss a series of topics (see above and below), all to prepare us for the launch of our booster club. We also have to participate in at least 5 community outreach events a semester (spring, summer, and fall)... practice, practice, practice! Lastly, we have to do a video diary series (a vlog)! Anyone that knows me, knows that I am geeking out over the vlog! I am so excited. What is even more exciting is that they sent us a tripod and light, so that it is quality recording. The moment I heard this, the ideas started to flow. I cannot wait to get started on this! Throughout the year we will also survey our community and identify the scientific needs of the community and write an outreach grant. Additionally, it comes with a $9000 stipend with the commitment of 50 hours a month (your PI has to sign off on it too). This opportunity is going to be able to provide me an idea of what doing #scicomm full time would be like. That is a huge advantage verses taking a job and finding out later that it is not right for me. The flu vaccine kit that was sent for the first semester of outreach. They also send you quarterly kits, made up of 2 community activities. These are really neat! This first set had a kit on flu vaccines (check out those little pigs!) and another on climate change, specifically on rising tides. I will write more on these kits and share material once I work through them! Whats even cooler, is that the fellowship helps you design your own activity. Your activity will then be sent out to booster clubs across the country! A kit is estimated to reach ~10,000 people... just amazing! If this all sounds as exciting as I think it does, I highly recommend you apply. They take applications from graduate students (masters and Ph.D.), Post-Docs, and adjunct faculty. I would be happy to share my successful application if you want to email me!

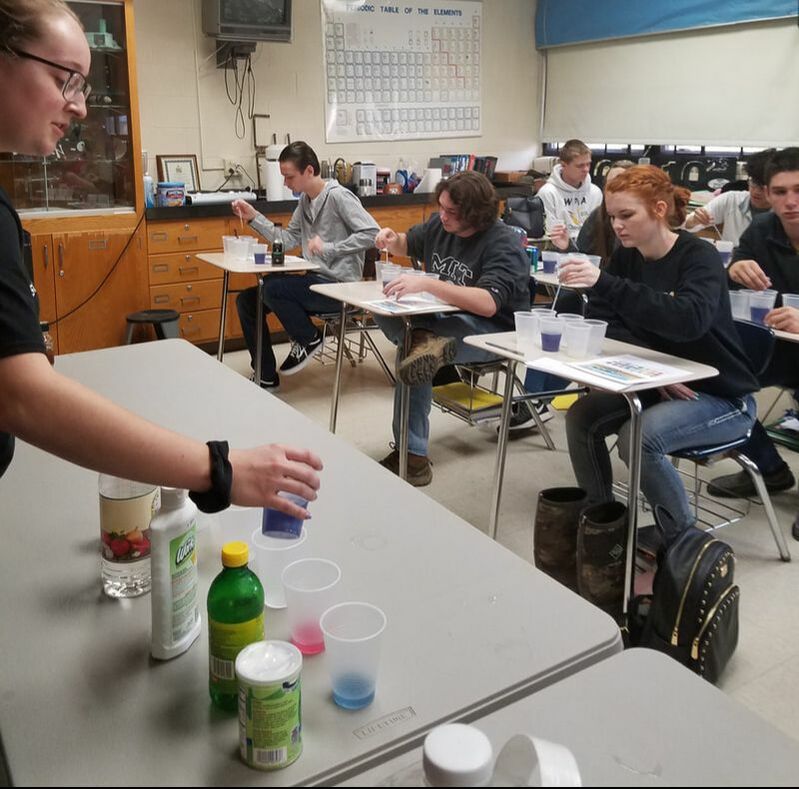

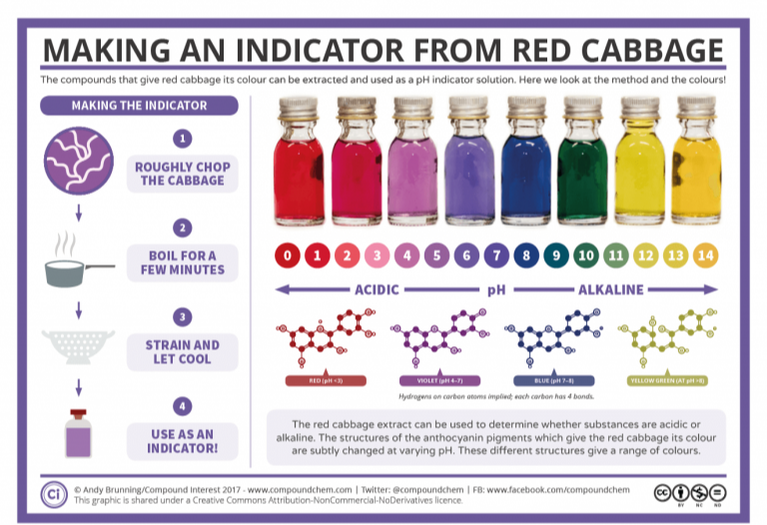

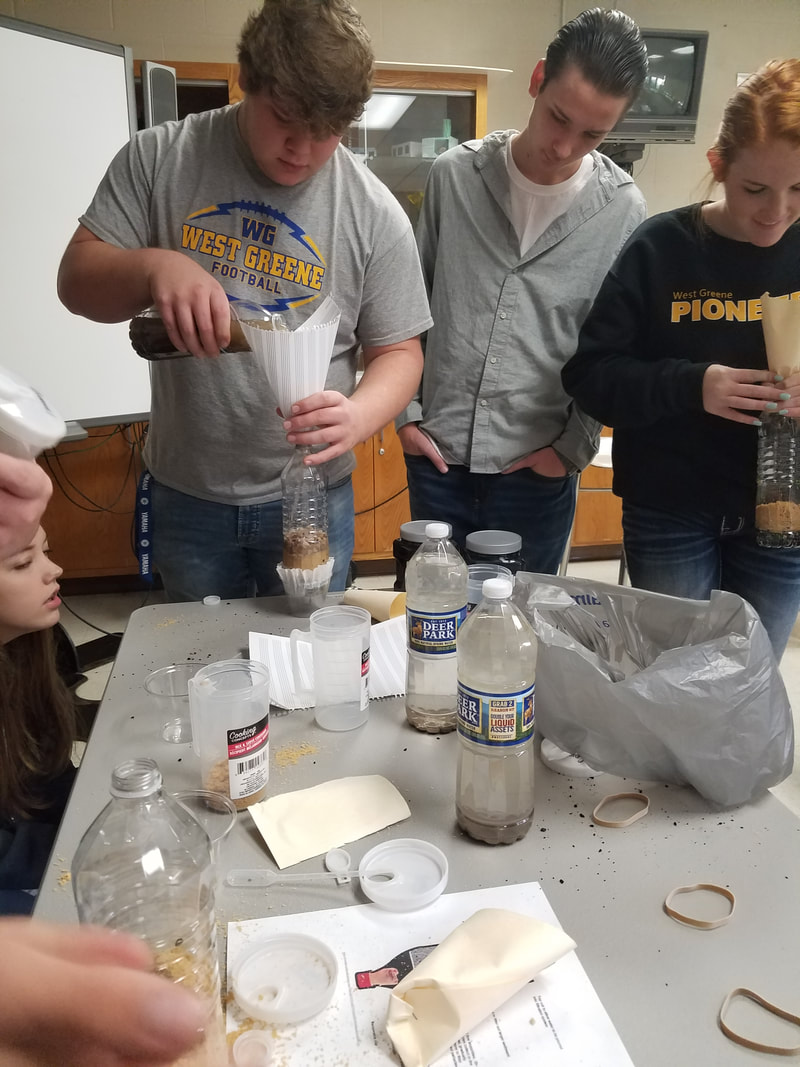

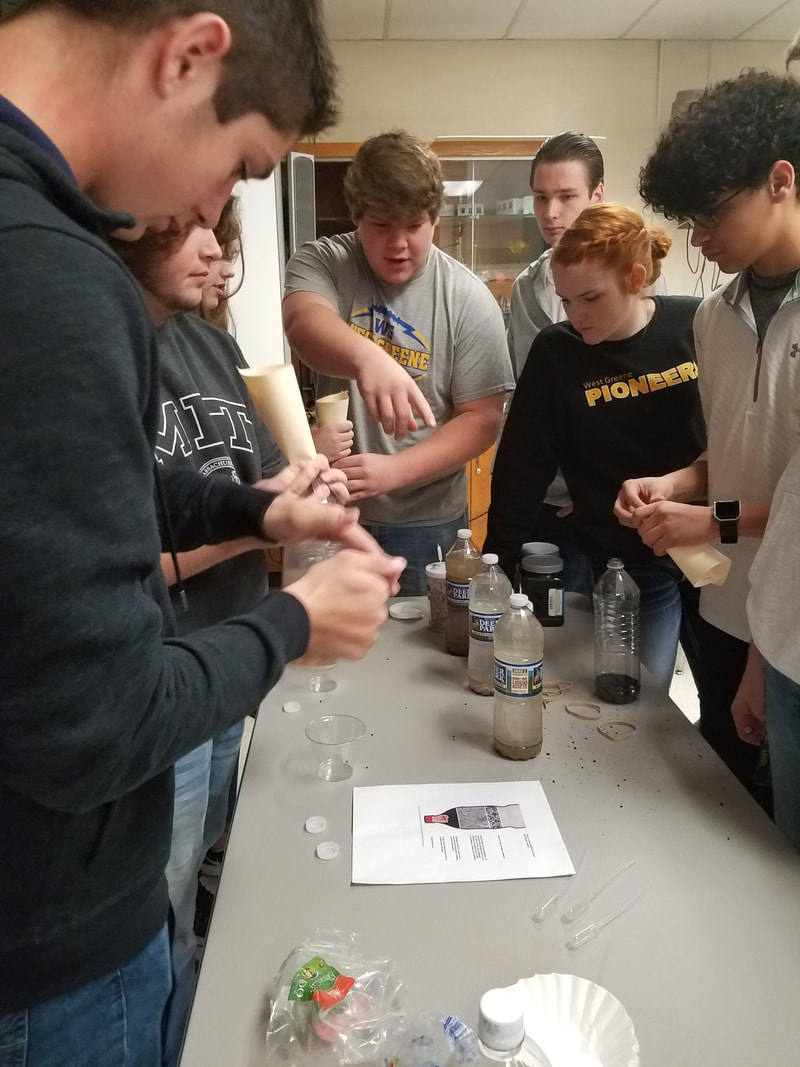

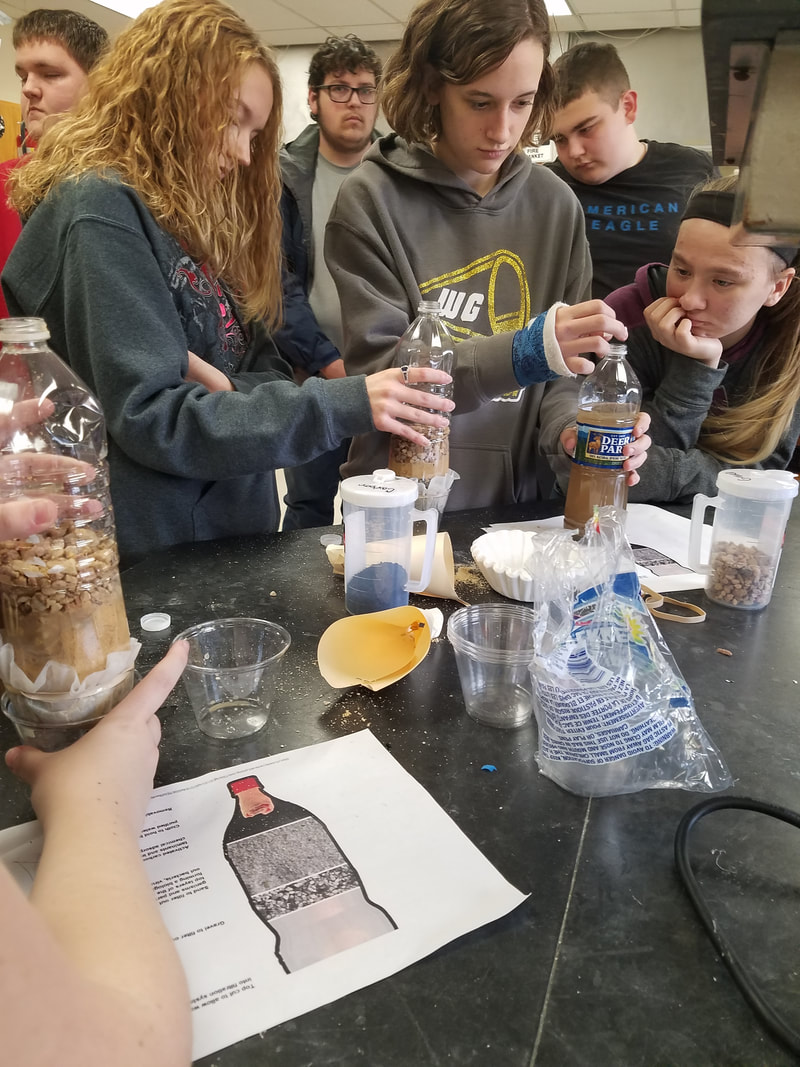

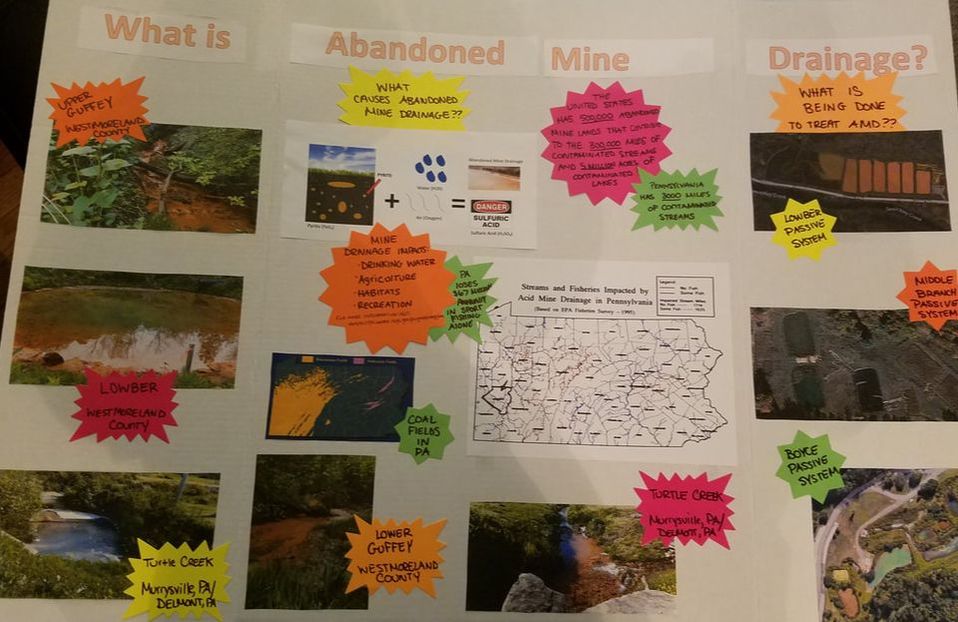

Women in Science at Duquesne University (WIS@DU) is an organization of women, from full professors to undergraduates, that strives to encourage and empower women of all ages. The organization holds seminars addressing common issues for women (and men!) such as negotiating, work-life balance, and time management. The organization also offers a mentor network for undergraduates, a place where students can participate in small group discussions on topics of interests and seek advice and guidance. Another large component of WIS@DU is STEM outreach. Due to the generous support of EQT Corporation, WIS@DU has been able to visit several schools in the greater Pittsburgh area. During these events, STEM departments across Duquesne University bring hands-on activities to local schools to help enrich the schools STEM Programs. These events have been a huge success, not only for the students but for the members of WIS@DU as well! This Fall WIS@DU visited West Greene High School in Greene County, Pennsylvania. This was an all day event where members of WIS@DU spent the morning at the school talking about local abandoned mine drainage (AMD) and then visited a local passive remediation system designed to treat AMD. The day started with a presentation by Dr. Nancy Trun, Associate Professor in the Biological Sciences Department at Duquesne University, on abandoned mine drainage (AMD), how AMD forms, and the devastation that occurs. She talked about how AMD comes in different forms (acidic and circum-neutral) and how there are different ways to treat AMD. Lead by Duquesne University graduate student Michelle Valkanas, the Women in Science (WIS@DU) group (Dr. Nancy Trun, Brianna Ports, Marisa Guido, Joanna Burton, and Mackenzie Martin) then did two in class activities. The first activity was a pH experiment that provided the students the ability to visualize the differences in pH. This activity was done using red cabbage, a natural pH indicator, and a series of household items going from very acidic to basic (lemon juice, floor cleaner, vinegar, baking soda, and antacids). The red cabbage was purple at circum-neutral (pH 7) and changed to red/pink at acidic pH (<4) and blue/green at basic pH (>8). Details on the red cabbage pH indicator can be found here. The second activity that WIS@DU did in the classroom was the building of a DIY water filter. This activity was done using only things that could be bought in the store: sand, pebbles, activated carbon, and a coffee filter. The students layered the carbon, sand, and pebbles into a 1 liter water bottle and filtered dirty water through the filter. The students were immersed in this activity, optimizing their filters and troubleshooting when the water was still coming out dirty! The students at West Greene High School try make their own water filters and brainstorm the most efficient way to construct them. We then went to visit a passive remediation system. Passive remediation systems are designed to treat AMD. There is a passive system, Maiden Mine, that is in Greene County less than an hour from the school. There we got a tour from Daniel Guy, an environmental scientist from Stream Restoration Inc., who discussed the different components of the passive system and how it works to remediate AMD. He even showed us the opening into the mine and took pH measurements throughout the tour to show the efficiency of the system. The students enjoyed the tour and one even asked Daniel for an internship at Stream Restoration Inc. this summer. Daniel from Stream Restoration showing the students what bituminous coal looks like! The opening of the Maiden Mine where you can see the iron hydroxide streamers and algae lining the top of the water (left) and Daniel from Stream Restoration talking to the students about the history of the mine and the technologies being used to restore the watershed (right). Students hiking across the system on their way to the biotic pond that comes before the wetlands. Women in Science members (left to right) Michelle Valkanas, Bri Ports, and Marisa Guido.

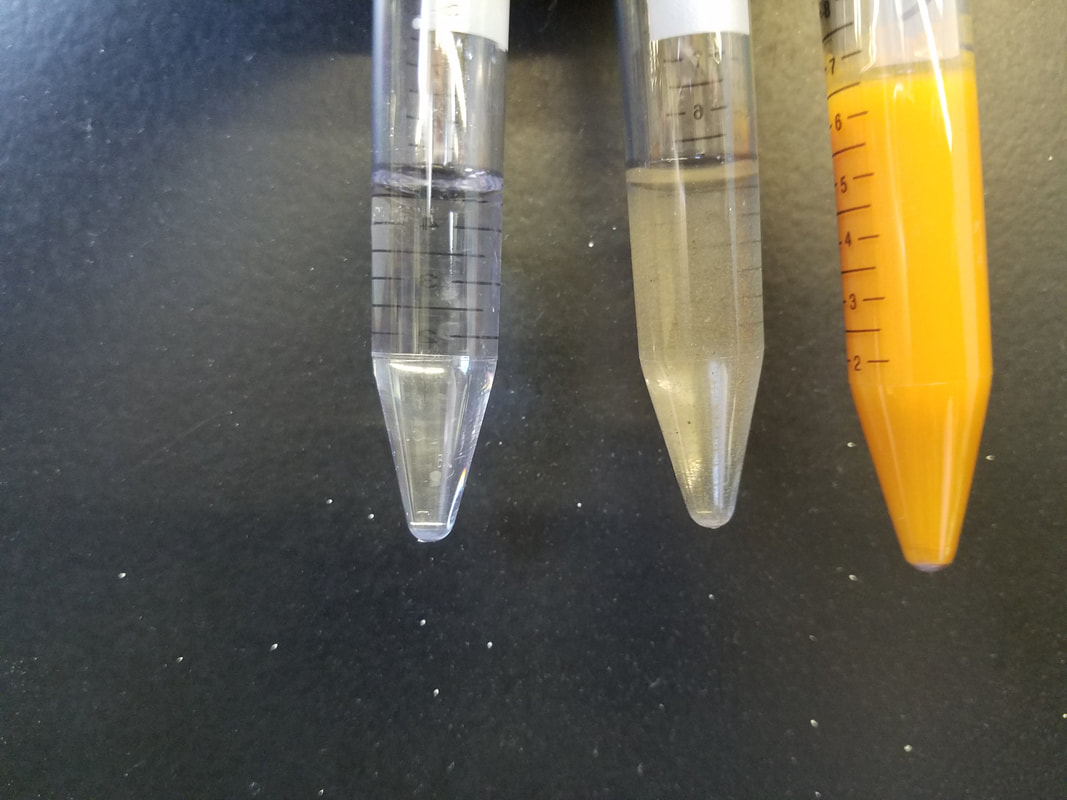

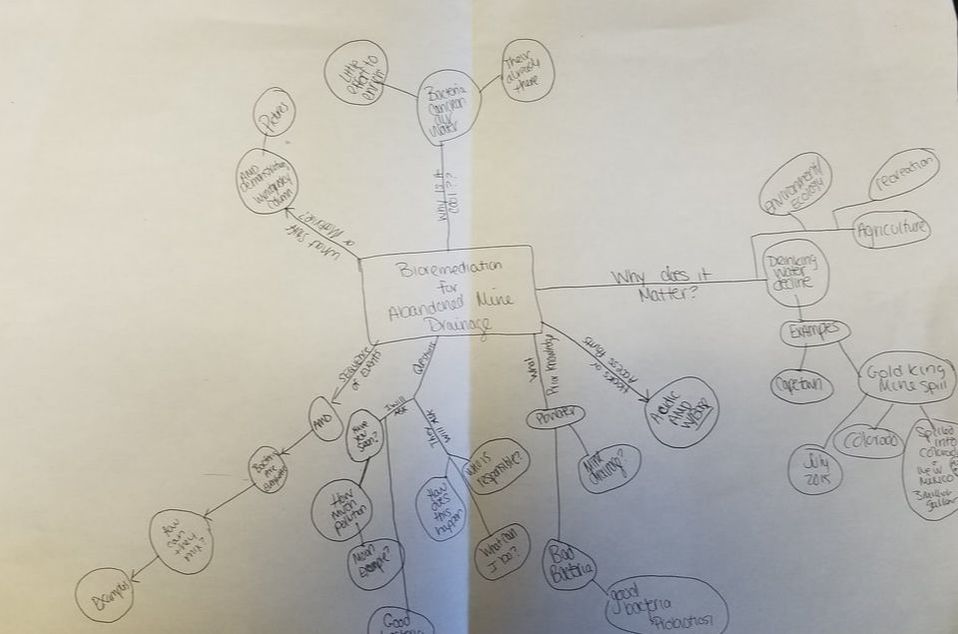

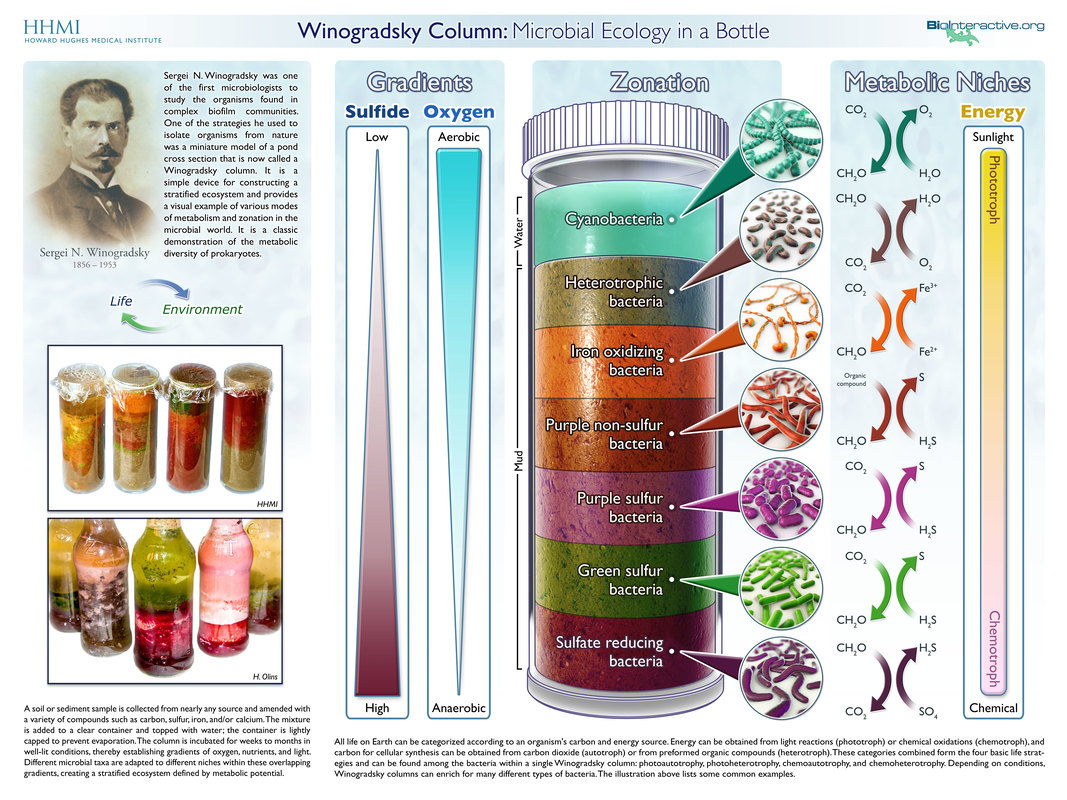

Science communication. I have been tossing around how to tackle this subject for sometime. I finally decided that I needed to stop thinking about it and just start writing. That is after all how things get done, right? I want to start off by saying that I lOVE science communication, this may make my views slightly biased. However, I still think a lot can be gleaned from what I am going to discuss. So what is science communication. It is exactly what is in the name. It is the communication of science. In a more specific definition, applying to an academic field, it typically refers to communicating science to the general public (non-experts). It is not limited to science, but really applies to all STEM fields. I also like to use it when talking about STEM outreach at schools. Science communication events can occur pretty much anywhere, but are commonly found at libraries, museums, non-profit events, and at high schools and middle schools. Women in Science at Duquesne University participating in a science communication event last spring; we presented a workshop called DNA-tastic, at a local Pittsburgh middle school. So what is the main objective? The main objective for science communication is to increase public awareness. The idea is to make science readily available and accessible. In order for science to be impactful, it needs to be understood. Good science communication takes complex ideas and presents them in a manner that is easy to understand. All ages can benefit from science communication, from young children with a limited STEM program in their school, to adults unaware of current scientific developments. STEM is a major component of all of our futures in some form or another and it is important that we understand what is currently developing and where we are going in the future. Additionally, science communication can raise awareness, in a fun approachable way. This is useful when tackling controversial subjects like global warming and evolution. There is a lot of fun ways to engage in science communication. I think it depends on what you feel comfortable with. Suzi Spitzer wrote a great blog on the five principles of science communication based on a science communication event held by the National Academy of Sciences she attended last fall. Of these points, my favorite is to "communicate with people, rather than to them"! I think that this is so important. People do not want to be talked at. Contaminated water demonstration. Three tubes of AMD (left picture) and the first tube after the pH was brought up with sodium hydroxide (right picture) Conversation is key. People are generally interested in engaging in STEM activities, they enjoy talking and learning about it. What they do not want is to be lectured. That is why I often find a fun activity, an eye catcher, that breaks the ice and gets people talking. For example, I take acidic mine drainage (AMD), that visually is clear, and place it among other forms of AMD that is visibly contaminated. I then ask people if they can identify the most contaminated sample and which one they think is the least contaminated. The clear sample is picked 9/10 times. I then bring up the pH by adding sodium hydroxide and watch everyones face in disbelief. The increase in pH causes all of the contamination to precipitate out (i.e. fall out) of solution. This then opens the door for conversation about AMD and how it is extremely prevalent in Pennsylvania and how you cannot always visually identify AMD. My concept map from the Science Communication Fellowship workshop at Phipps Conservatory. Science communication takes practice. As scientist, we are often immersed in our work, living and breathing science ALL THE TIME. This sometimes make it difficult to talk about it in a way that non-experts can understand. That is why, I believe, that it is important to not only engage in science communication (practice makes perfect), but to try to find workshops or fellowships to better train you in science communication. When I first started participating in science communication outreach events, I thought that I was doing a great job. That I was effectively disseminating my science in a way that people could understand. It was not till I participated in a Science Communication Fellowship program at Phipps Conservatory, that I realized that I was still presenting a technical presentation, not a conversation. Dr. Sarah States and Dr. Maria Wheeler-Dubas led a one day workshop, where we did a series of activities that helped to tease apart our science in a way that could be easily understood. The workshop was divided into 5 topics, all of which had several activities within it. 1. The complexity of exchanging information It was in this first session that we talked about what we "bring to the communication table". We talked about different types of stakeholder groups and how it is important to understand each's groups motivation, before, engaging in communication. That you needed to know where people were coming from, to be able to connect with them. Stakeholders can be government/local agencies, communities, companies, or an individual. The stakeholders involved depends on the topic and it is important that you think of all those that have a stake in your research so that you are prepared to talk to anyone in an informative manner. 2. Creating a more accessible message Then we went on to work on the message we were hoping to disseminate. We talked about knowing your audience. That each individual comes to you with previous knowledge and/or opinions. It is important to be aware of this, so you can communicate in the most effective way. Ways to discuss your science thru a story was also discussed. It was emphasized that people connect well to stories. This was a very effective exercise. Lastly, we did an exercise that was called, "What's in a Word". It was a challenging exercise, but probably the most useful thing I did that day (and my favorite!). We were given a worksheet that had three columns (term, meaning, and alternative word) and several blank rows. We were told to fill in terms commonly used in our field and then challenged to find alternatives that would be more easily received. It really made me realize that even when I thought I was removing jargon from my presentation, I was not. I really encourage EVERYONE to try this exercise. 3. Meaningful and impacting science engagement We then moved on to making a concept map. This allowed us to brainstorm a toolkit that covers all aspects of successfully engaging with public. We also did a role playing game, where we presented our elevator pitches and the others in the group would act like different "stake holders", asking each other questions. It was very useful to be probed with questions. It not only brought to light when I was not effectively portraying my science, but brought up things I did not think of. For example, I was asked in this exercise "what they could do to help". I was so use to presenting my science at academic conferences, it did not occur to me that individuals may want to get involved! How excited I was to go home and find an answer to that question. 4. Sharing your own science story It was in this section that we worked on our own story. The instructors explained that often the audience is looking to trust you and that it is thru sharing personal stories that trust can be gained. They encouraged us to think of our journey, why did we get into science and how/why are we studying what we do. They also shared a list of writing tips, that could be used to form your elevator pitch and your science story. 5. Tabling and table aesthetics Lastly they talked about tabling. I was tasked to develop a table event to communicate my science. This is referred to as "tabling". The idea of tabling is that you setup an interactive display that people can interact with, while talking with you, the scientist, about your topic. The display should be visually appeasing and eye-catching. It should have staggered layers, rather than being uniform in height. It should have bright colors and items that can be picked up and played with. Tabling is commonly seen in science communication events. My table display at Meet a Scientist event at Phipps Conservatory in May 2018. A close up of my poster board on abandon mine drainage in Pennsylvania. My table was on abandon mine drainage in Pennsylvania, specifically in southwestern Pennsylvania. I had a poster board that had pictures of local devastation caused by AMD. This allowed people to relate to the problem, as this was occurring in the areas they were familiar with or even lived in. I then had a series of Winogradsky columns of different sizes, from big ones that showed great detail to small ones that were in 50ml conical tubes that could be picked up and analyzed. Winogradsky columns are a great science communication tool because it allows people to see a diverse group of bacteria in a safe manner. It is also a fun DIY activity that people can do at home. I had printed instructions on how to make your own DIY Winogradsky column at home. I have adapted the instructions from here and then attached a great reference image for the kids to identify different kinds of bacteria. I also had the clear water demonstration (explained above), to grab everyone's attention. Reference image I sent home with DIY Winogradsky Columns. Printed from: www.hhmi.org/biointeractive/poster-winogradsky-column-microbial-evolution-bottle Once I completed my table display, I brought the display back for Maria to look over and approve my display. She was extremely encouraging and gave great tips and suggestions! (Seriously, Maria is fantastic! I highly recommend following her on twitter, she is always posting useful science communication tips and events). Then I was ready to participate in a Meet a Scientist event. I participated in a small interview with Maria, that was posted on Phipps website promoting the event. Presenting my science at the Meet a Scientist event, May 2018. Nothing is better than wearing a lab coat! Meet a Scientist, May 2018. The Meet a Scientist event was setup in one of the rooms at Phipps Conservatory where patrons could stop and visit my exhibit. It was a really engaging experience that allowed me to interact with not only children, but adults as well. We talked about abandoned mine drainage and how Pennsylvania has over 3,000 miles of contaminated watersheds. I had a list of resources if individuals wanted to know more and contact information for non-profit organizations that were working to restore the environmental systems. Hands-on is an important aspect to every science communication event. Me at my table, during Meet a Scientist event at Phipps Conservatory It was my experience participating in the Science Communication Fellowship that I truly developed a love for science communication. I think that it is so incredibly important. The problem is that, so often, as scientist we are constantly pressured to perform (grants, papers, results.. results.. results..), that we leave no time for service. I believe that it is our responsibility as scientist to effectively communicate our findings to not only colleagues (i.e. experts), but to non-experts as well. That funding agencies and departments should reward individuals effectively finding a balance between scientific success and service (science communication). We should also be encouraging undergraduates, matter of fact, training undergraduates to participate in science communication. I always make sure to have several undergraduates participate in events that I plan. It really benefits the student, giving them practice in communicating the science that they are learning, without becoming overwhelmed with jargon and intricate details. As we continue to progress farther in to the world of robotics, genome editing, and nanoparticles, it is more important than ever to have science communication. People need to not only understand the progressive world we live in, but that everyday people are making revolutionary discoveries and that its not a mad scientist in an ivory tower.

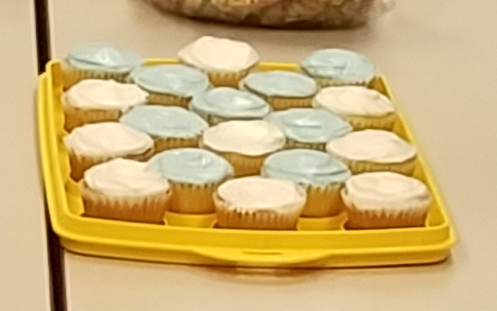

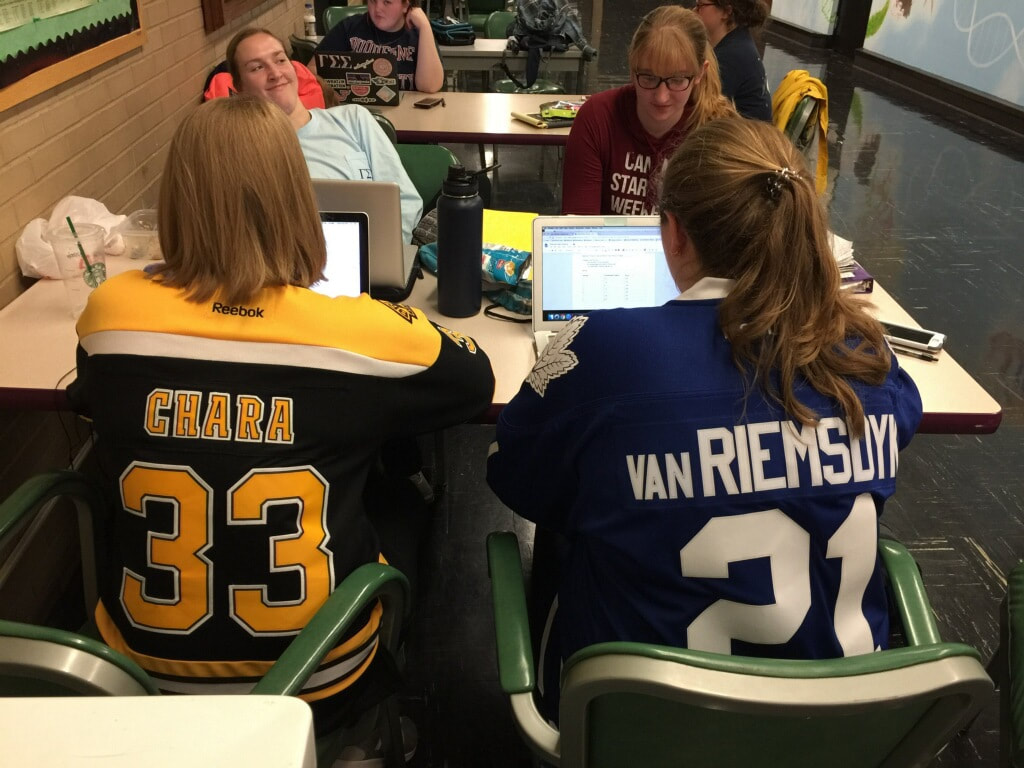

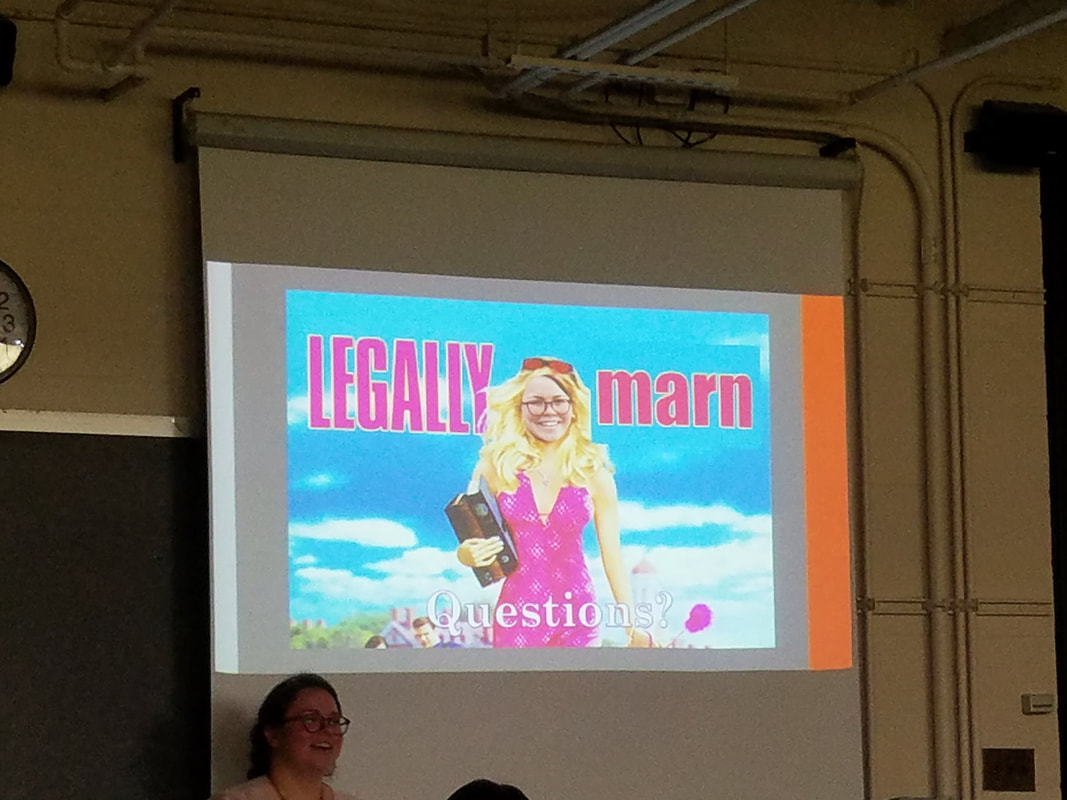

As the semester came to a close, I found myself with mixed emotions. Part of me was relieved, the semester was extremely busy and somewhat chaotic, I will now have so much more time to do research-uninterrupted research (the best kind!). On the other hand, I was going to miss the students and the awesome work that they were doing in class. As we gathered for our annual end of semester party, the excitement the students had for the class continued to show. One student made blue and white cupcakes, signifying the blue/white screen we had performed in class during transformations, and the white cupcakes even had an insert (cookie) inside! Another student had made dirt dessert in the form of our AMD site that we had visited earlier in the semester. These clever, and delicious, desserts not only exemplified their creativity, but their appreciation for a great semester. It was indeed a great semester! In fact, I spent most of the semester bragging about the students. I found myself telling everyone about the great projects that they had developed. The blue and white cupcakes, signifying the blue/white transformation screen. The students were given 10 weeks to design and execute a research project involving microbial communities found in abandoned mine drainage. This particular group of students, took the challenge and hit the ground running. Not only was there a nice mix of individual projects, but the students became invested in their projects right from the start. It was amazing to see the growth the students had over the course of the semester, not just growth in laboratory skills and knowledge, but personal growth. I watched individuals who struggled with confidence thrive, introverts come out of their shell, and organizational and planning skills meet optimum levels. It was extremely rewarding to see the students immerse themselves in their science. Dirt dessert in the form of Lowber Passive Remediation System So what are these great projects? I am so glad you asked! This semester some of the students isolated manganese and iron bacteria and identified them through Sanger sequencing. Others isolated bacteria from Lowber soil and compared it to soil from Duquesne. They than tested the isolated bacteria from both locations for metal resistance. Two groups looked at antibiotic resistance in bacteria isolated from Lowber compared to lab strains. Though there did not appear to be an increase in antibiotic resistance in bacteria isolated from the AMD, the students did find that lab strain Serratia marcescens exhibited increase resistance when grown in media made with AMD! The students were so excited about their findings that they are continuing their project this summer. Other students looked at rhizosphere bacteria and the role they play in detoxifying the area around the plant roots. Another project that is being continued by the students next semester in our lab, is a study comparing sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB) found at Lowber (circum-neutral discharge) and Middle Branch (acidic discharge). The students worked this semester on isolating SRBs from both locations, and will identify them and run comparison tests next semester. A student going to grad school in the fall for bioinformatics (Go Nicole!), took her interest in bioinformatics and used 16S sequencing analysis to compare two passive systems to see if their populations were similar. She then focused on iron and sulfur bacteria to see if there was a significant difference between the two. Despite their differences, there was teamwork even during the playoffs!!Another student performed a series of stains on the bacteria from across the remediation site. This was right in her wheel house as this is what she is going to grad school for in the fall (YAY!). It was nice to see her incorporate her passions and interests into her independent project. Lastly, a student compared water and bacteria from upstream and downstream of the effluent from the passive system. She is going to law school in the fall, but remained a hard-working, dedicated scientist to the very last minute of class. Marnie's transition from a scientist to a law student! At the end of the semester the students presented their independent projects to the class in a powerpoint presentation. It was truly enjoyable watching them present their work. The students went above and beyond this semester to complete their projects and this was evident as they presented their work. I am so proud of all them! So as the mixed emotions tossed and turned inside of me, I had a moment of clarity. I am a teacher, yes it is what I am contracted to do, but it is more than that. I am invested in the success of my students. I want to see everyone of them succeed and I celebrate their victories and stand by them in their defeats. I wasn't sure if I was going to like teaching, but it has become clear - I do! I am looking forward to the future where I get to do it all over again. Teaching truly is a rewarding experience. The Superlab IV 2018 students celebrating at the end of the semester party

I remember the first time that I participated in novel research. How excited I was! That excitement quickly turned to pure terror. What do you mean no one has ever answered this question? We do not know the outcome? How do I know I am right? What happens if I am wrong? As I continued, I gained confidence in myself and in my work. It was then that I realized that this was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life, to seek out the unknown and make a difference through scientific discovery. This was my senior year of undergrad at Duquesne University and I was taken a 4 credit lab course, that has been coined "superlab". Superlab comes in 2 parts, the first semester everyone takes the same course where the students are introduced to a range of lab techniques involving classic microbiology, molecular biology, and protein purification. The second semester comes in several concentrations (physiology, cell biology, and microbiology) where the students are exposed to an in-depth look at a specific topic. I had enrolled in Dr. Nancy Trun's microbiology superlab. This course provides the unique opportunity to engage in novel research, allowing the students to experience science in a way that they typically are not exposed too. They develop hypotheses, design experiments to test these hypotheses, and carry out the designed experiments. Allowing the students to "take the wheel" of their own education, encourages active involvement in the learning experience. They are not just going through the motions, in fact, each individual is creating their own path. I credit this course for the reason that I am in graduate school obtaining a Ph.D. with a concentration in microbiology. Everybody loves field trip day! Brady, Benita, and Natalie (left to right) on the deck that crosses over the effluent. I now have the opportunity to be a teaching assistant in the very lab course that inspired me to be where I am today. It provides me the unique perspective that allows me to relate with the students on a more personal level, as I was in their shoes not to long ago. I see the excitement and I see the fear. It is definitely a rollercoaster of emotions (for the students and myself), becoming a scientist is no easy feat! But the students quickly adapt and develop solid hypotheses and execute sound experimental design. It is truly a joy watching the students gain confidence and rise to the challenge, surpassing all of their (and mine) expectations. Lowber Passive Remediation System. The class focuses on bioremediation, specifically involving passive remediation systems designed to treat coal mine drainage . The students learn about passive systems, what is known, and what remains unknown. Over the course of the first 6 weeks they form hypotheses and design experiments. Then comes my favorite day of the semester.... (*drum roll please*) FIELD TRIP DAY. We get to take the students to a remediation site (Lowber, see "Field Sites") so that they can collect their own samples. This is always such a fun day, the students really enjoy being in the field. Its funny to hear what the students think the site was going to be like, one student said to me "I thought you climbed deep down into a cave to get to the site". I am sure spelunking was never mentioned in class! Melissa (left) came ready to go in her boots and fanny pack, while Dania (right) took more of a fashion forward approach, staying pretty in pink. I am not the only one that gets excited about field trip day, the students do too! Some students came decked out, ready to climb directly into the remediation site, while others were not quite sure what to expect. We started the day with a little background about the site, where Dr. Trun explained how the system worked and what to expect as we moved down through the system. The source pond, where the discharge surfaced from under ground, was a distinct green color. This pond contains high levels of iron and sulfate and has not yet had a chance to precipitate any of the iron. That will quickly change as it moves through the system, turning all of the ponds a bright orange color. Dr. Trun talks to the students about Lowber and how the passive remediation system works After the talk, we moved to the end of the system. That way we could work from the effluent, the end of the wetlands, back up to the beginning of the system (where our cars were). Along the way, I noticed that the ponds were orange well into the wetlands. This is not usually the case, but February has had a record amount of rainfall, ~5" alone in the week before we came out. Heavy rainfall increases flow rate, decreasing retention time and does not allow enough time for contaminants (iron especially) to precipitate out. Even the effluent remained tainted with orange. The yellow boy (orange water) continuing well into the wetlands. Even after passing through the entire system, the effluent remained orange. The students really jumped in (some literally) and began to sample. All together we collected 50L of water across all of the 6 settling ponds, the wetlands, and the source pond. The samples will be used to make media, be plated on a variety of selective media types, stained to identify morphology and biochemical properties of bacteria present, and enriched to isolate sulfur, manganese, and iron bacteria. Plant growth and the relationship with rhizosphere bacteria, as well as Sewickley Creek were also sampled for further analysis. The class disperses with bottles in hand. Melissa just jumped right in and began to sample the wetlands. Ali using the sampling pool to get a slurry sample.. Rasha sampling in pond 1. She really took a liking to sampling, jumping at every opportunity to collect slurry. The system looked so much different from when I was here in January. Everything had thawed, the geese had returned, and biofilms were becoming more prevalent. As we moved from pond to pond, I tried to point out all of the changes that were occurring. Soon, the algae and cyanobacteria will begin to bloom and the wetlands will return to green. Spring is near! Biofilms forming entering into pond 4 (left) and on the shore of pond 2 (right). The geese have returned in preparation for spring. The weather was beautiful and the field trip was a success. The students got to witness the devastation that was happening as a result of abandoned coal mine drainage (AMD). This leads the students to be even more invested in finding possible solutions to treating AMD. It is through this experience, that we (as educators) are able to take what was taught to them in class and materialize it in a way that you can't possibly experience in a classroom.

There is something so beautiful about an early morning following a winter snowfall. There is a sense of purity, for a few moments everything is new and untouched. The air appears cleaner and the world seems still. As Elizabeth Cochran, a masters student in my lab, and I approached Lowber I got a sense of peace, the remediation site had transferred from a place of destruction to a place of beauty overnight. Thats not to say that the devastation that was happening to the land was forgotten (the orange ponds were still prominent), but for one moment the land was once again beautiful, it was breathtaking. Lowber passive remediation system in Lowber, PA (Winter 2018) Picture taken in one of the troughs between the ponds We started at the effluent of the system, the end of the wetlands, and worked our way forward. The wetlands was primarily frozen, but there was still water flowing through a narrow path. It made me wonder if the water was flowing underneath the ice or if water flow was truly limited to a narrow path all year. I think a dye test may be in order this summer to test the water flow from influent to effluent. In the mean time, the water was muddy and not very clear. Elizabeth taking field measurements in the wetlands (effluent) Frozen wetlands Lowber now showing its rendition of Swan Lake After we sampled 6 liters of water/soil slurry, took field measurements, and freed a cattail from a block of ice, we moved to pond 3. Pond 3 is in the middle of the remediation system and we often study this pond because it serves as a potential inflection point (where contaminants and microbial communities shift). Pond 3 had no ice at all and was six degrees warmer than the effluent. This is to be expected, as the first couple ponds typically don't freeze because the mine discharge is from an underground mine and so it comes into the system fairly warm all year round. There was a few biofilms present as well. Another 6 liters of slurry was collected and Elizabeth found another interesting plant to sample for iron accumulation around the roots. Pond 3 with no ice Biofilms found in Pond 3 Here I am taking field measurements in pond 3 Our last stop was pond 1 where another 6 liters of slurry was collected and field measurements were taken. Pond 1 is the first settling pond of the system and was even warmer than pond 3 (~3 degrees warmer). There was a large manganese sheen at the influent of pond 1, suggesting the presence of leptothrix. There was also extensive biofilms growing around the edge of the pond. There was visible bubbles coming from the biofilms. There was a a distinct smell of "rotten eggs", the classic description of sulfide, present at this pond, where the other ponds lacked this lovely smell. Pond 1 and its massive manganese sheen Biofilm formation in pond 1, note the bubbles coming up to the surface As we were walking past the giant mound of iron hydroxide that had been drudged from the ponds (that was now covered in snow), we noticed that there were crystals forming in the snow. Though I cannot explain what was causing this crystallization, it was really cool seeing them laying in the snow! It just confirmed the beauty that had formed at Lowber that cool winter morning. Crystal formation on top of the iron hydroxide that had been drudged from the ponds close up of the crystals The samples collected on this trip will be used for enrichment cultures and lab-based studies to identify bacteria that may serve as bioindicators, as well as bacteria that may be resolubilizing contaminants in the system. mRNA will also be sequenced to track changes in metabolic genes, that could later be used to identify changes/shifts in the system.

|

Michelle ValkanasI will blog here about research excursions, community outreach, and other exciting science events Archives

March 2019

Categories |

Copyright © 2024 by Michelle M. Valkanas. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed