|

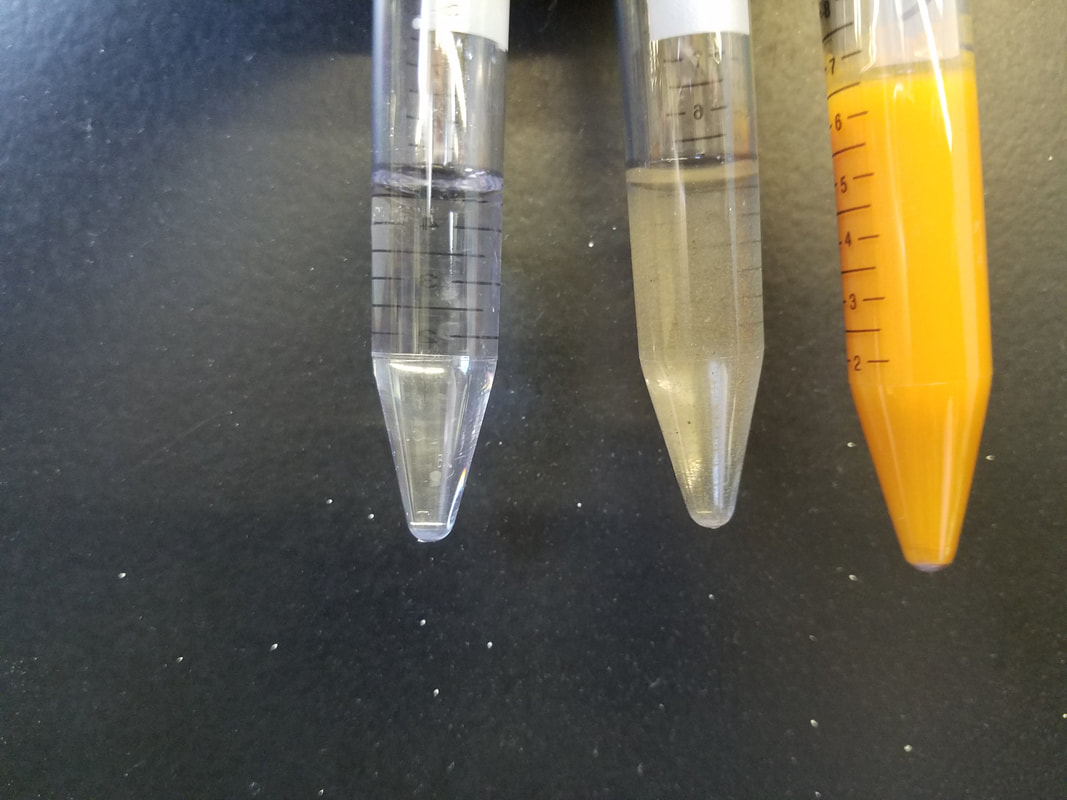

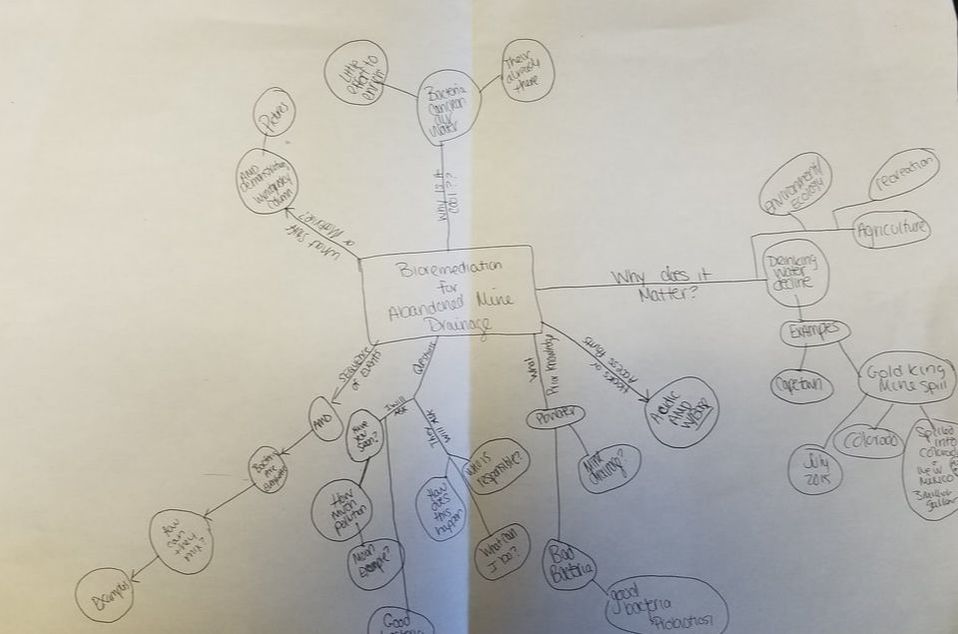

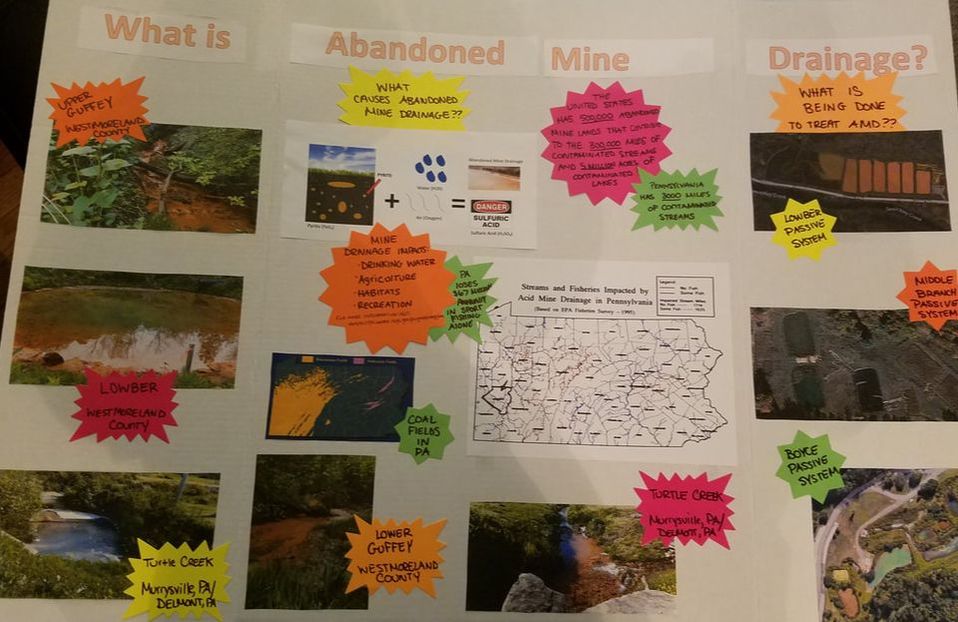

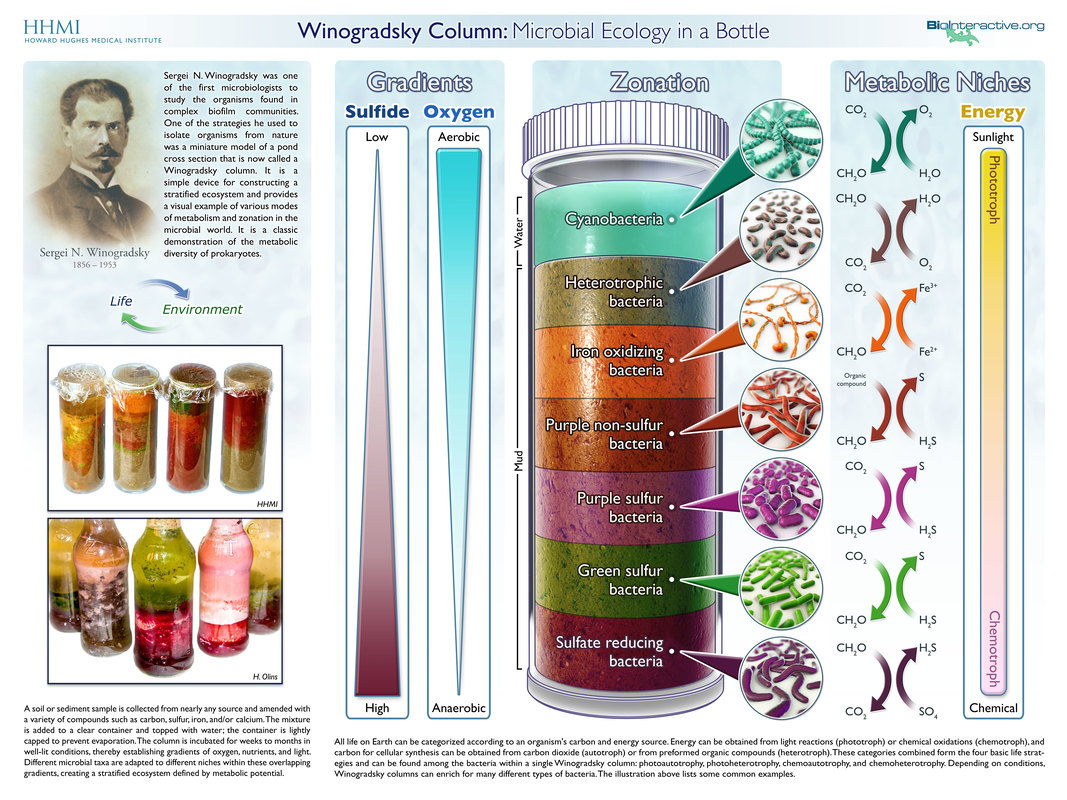

Science communication. I have been tossing around how to tackle this subject for sometime. I finally decided that I needed to stop thinking about it and just start writing. That is after all how things get done, right? I want to start off by saying that I lOVE science communication, this may make my views slightly biased. However, I still think a lot can be gleaned from what I am going to discuss. So what is science communication. It is exactly what is in the name. It is the communication of science. In a more specific definition, applying to an academic field, it typically refers to communicating science to the general public (non-experts). It is not limited to science, but really applies to all STEM fields. I also like to use it when talking about STEM outreach at schools. Science communication events can occur pretty much anywhere, but are commonly found at libraries, museums, non-profit events, and at high schools and middle schools. Women in Science at Duquesne University participating in a science communication event last spring; we presented a workshop called DNA-tastic, at a local Pittsburgh middle school. So what is the main objective? The main objective for science communication is to increase public awareness. The idea is to make science readily available and accessible. In order for science to be impactful, it needs to be understood. Good science communication takes complex ideas and presents them in a manner that is easy to understand. All ages can benefit from science communication, from young children with a limited STEM program in their school, to adults unaware of current scientific developments. STEM is a major component of all of our futures in some form or another and it is important that we understand what is currently developing and where we are going in the future. Additionally, science communication can raise awareness, in a fun approachable way. This is useful when tackling controversial subjects like global warming and evolution. There is a lot of fun ways to engage in science communication. I think it depends on what you feel comfortable with. Suzi Spitzer wrote a great blog on the five principles of science communication based on a science communication event held by the National Academy of Sciences she attended last fall. Of these points, my favorite is to "communicate with people, rather than to them"! I think that this is so important. People do not want to be talked at. Contaminated water demonstration. Three tubes of AMD (left picture) and the first tube after the pH was brought up with sodium hydroxide (right picture) Conversation is key. People are generally interested in engaging in STEM activities, they enjoy talking and learning about it. What they do not want is to be lectured. That is why I often find a fun activity, an eye catcher, that breaks the ice and gets people talking. For example, I take acidic mine drainage (AMD), that visually is clear, and place it among other forms of AMD that is visibly contaminated. I then ask people if they can identify the most contaminated sample and which one they think is the least contaminated. The clear sample is picked 9/10 times. I then bring up the pH by adding sodium hydroxide and watch everyones face in disbelief. The increase in pH causes all of the contamination to precipitate out (i.e. fall out) of solution. This then opens the door for conversation about AMD and how it is extremely prevalent in Pennsylvania and how you cannot always visually identify AMD. My concept map from the Science Communication Fellowship workshop at Phipps Conservatory. Science communication takes practice. As scientist, we are often immersed in our work, living and breathing science ALL THE TIME. This sometimes make it difficult to talk about it in a way that non-experts can understand. That is why, I believe, that it is important to not only engage in science communication (practice makes perfect), but to try to find workshops or fellowships to better train you in science communication. When I first started participating in science communication outreach events, I thought that I was doing a great job. That I was effectively disseminating my science in a way that people could understand. It was not till I participated in a Science Communication Fellowship program at Phipps Conservatory, that I realized that I was still presenting a technical presentation, not a conversation. Dr. Sarah States and Dr. Maria Wheeler-Dubas led a one day workshop, where we did a series of activities that helped to tease apart our science in a way that could be easily understood. The workshop was divided into 5 topics, all of which had several activities within it. 1. The complexity of exchanging information It was in this first session that we talked about what we "bring to the communication table". We talked about different types of stakeholder groups and how it is important to understand each's groups motivation, before, engaging in communication. That you needed to know where people were coming from, to be able to connect with them. Stakeholders can be government/local agencies, communities, companies, or an individual. The stakeholders involved depends on the topic and it is important that you think of all those that have a stake in your research so that you are prepared to talk to anyone in an informative manner. 2. Creating a more accessible message Then we went on to work on the message we were hoping to disseminate. We talked about knowing your audience. That each individual comes to you with previous knowledge and/or opinions. It is important to be aware of this, so you can communicate in the most effective way. Ways to discuss your science thru a story was also discussed. It was emphasized that people connect well to stories. This was a very effective exercise. Lastly, we did an exercise that was called, "What's in a Word". It was a challenging exercise, but probably the most useful thing I did that day (and my favorite!). We were given a worksheet that had three columns (term, meaning, and alternative word) and several blank rows. We were told to fill in terms commonly used in our field and then challenged to find alternatives that would be more easily received. It really made me realize that even when I thought I was removing jargon from my presentation, I was not. I really encourage EVERYONE to try this exercise. 3. Meaningful and impacting science engagement We then moved on to making a concept map. This allowed us to brainstorm a toolkit that covers all aspects of successfully engaging with public. We also did a role playing game, where we presented our elevator pitches and the others in the group would act like different "stake holders", asking each other questions. It was very useful to be probed with questions. It not only brought to light when I was not effectively portraying my science, but brought up things I did not think of. For example, I was asked in this exercise "what they could do to help". I was so use to presenting my science at academic conferences, it did not occur to me that individuals may want to get involved! How excited I was to go home and find an answer to that question. 4. Sharing your own science story It was in this section that we worked on our own story. The instructors explained that often the audience is looking to trust you and that it is thru sharing personal stories that trust can be gained. They encouraged us to think of our journey, why did we get into science and how/why are we studying what we do. They also shared a list of writing tips, that could be used to form your elevator pitch and your science story. 5. Tabling and table aesthetics Lastly they talked about tabling. I was tasked to develop a table event to communicate my science. This is referred to as "tabling". The idea of tabling is that you setup an interactive display that people can interact with, while talking with you, the scientist, about your topic. The display should be visually appeasing and eye-catching. It should have staggered layers, rather than being uniform in height. It should have bright colors and items that can be picked up and played with. Tabling is commonly seen in science communication events. My table display at Meet a Scientist event at Phipps Conservatory in May 2018. A close up of my poster board on abandon mine drainage in Pennsylvania. My table was on abandon mine drainage in Pennsylvania, specifically in southwestern Pennsylvania. I had a poster board that had pictures of local devastation caused by AMD. This allowed people to relate to the problem, as this was occurring in the areas they were familiar with or even lived in. I then had a series of Winogradsky columns of different sizes, from big ones that showed great detail to small ones that were in 50ml conical tubes that could be picked up and analyzed. Winogradsky columns are a great science communication tool because it allows people to see a diverse group of bacteria in a safe manner. It is also a fun DIY activity that people can do at home. I had printed instructions on how to make your own DIY Winogradsky column at home. I have adapted the instructions from here and then attached a great reference image for the kids to identify different kinds of bacteria. I also had the clear water demonstration (explained above), to grab everyone's attention. Reference image I sent home with DIY Winogradsky Columns. Printed from: www.hhmi.org/biointeractive/poster-winogradsky-column-microbial-evolution-bottle Once I completed my table display, I brought the display back for Maria to look over and approve my display. She was extremely encouraging and gave great tips and suggestions! (Seriously, Maria is fantastic! I highly recommend following her on twitter, she is always posting useful science communication tips and events). Then I was ready to participate in a Meet a Scientist event. I participated in a small interview with Maria, that was posted on Phipps website promoting the event. Presenting my science at the Meet a Scientist event, May 2018. Nothing is better than wearing a lab coat! Meet a Scientist, May 2018. The Meet a Scientist event was setup in one of the rooms at Phipps Conservatory where patrons could stop and visit my exhibit. It was a really engaging experience that allowed me to interact with not only children, but adults as well. We talked about abandoned mine drainage and how Pennsylvania has over 3,000 miles of contaminated watersheds. I had a list of resources if individuals wanted to know more and contact information for non-profit organizations that were working to restore the environmental systems. Hands-on is an important aspect to every science communication event. Me at my table, during Meet a Scientist event at Phipps Conservatory It was my experience participating in the Science Communication Fellowship that I truly developed a love for science communication. I think that it is so incredibly important. The problem is that, so often, as scientist we are constantly pressured to perform (grants, papers, results.. results.. results..), that we leave no time for service. I believe that it is our responsibility as scientist to effectively communicate our findings to not only colleagues (i.e. experts), but to non-experts as well. That funding agencies and departments should reward individuals effectively finding a balance between scientific success and service (science communication). We should also be encouraging undergraduates, matter of fact, training undergraduates to participate in science communication. I always make sure to have several undergraduates participate in events that I plan. It really benefits the student, giving them practice in communicating the science that they are learning, without becoming overwhelmed with jargon and intricate details. As we continue to progress farther in to the world of robotics, genome editing, and nanoparticles, it is more important than ever to have science communication. People need to not only understand the progressive world we live in, but that everyday people are making revolutionary discoveries and that its not a mad scientist in an ivory tower.

0 Comments

|

Michelle ValkanasI will blog here about research excursions, community outreach, and other exciting science events Archives

March 2019

Categories |

Copyright © 2024 by Michelle M. Valkanas. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed